Background

This paper is based on research which I did in 2006, leading to the publication of the results as two articles (18,000 words) in the Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research (Volume 87 Number 350 in Summer 2009 and Volume 87 Number 352 in Winter 2009). I also gave it as a PowerPoint presentation to the Research Section of the Napoleonic Association, and this paper is based on that Powerpoint presentation, but with a bit of extra detail from the full paper.

The subject of this was the Authorised Establishments of the British Army during the Napoleonic Wars. That is the number of officers, NCOs and soldiers that each unit was supposed to have, as opposed to their actual strengths.

It arose out of an online conversation which I had on the Napoleon Series Forum with the distinguished military historian and wargamer, George Nafziger, in which he said that he could never understand British Army organisation of the Napoleonic era, since there seemed to be no structure to it. Since I had written British Army establishments during my Army service, I felt that this was unlikely, so I researched the subject.

General

If you look at any other army during this period it is relatively easy to find secondary sources giving their authorised strengths.

The French for example in 1808 had infantry regiments of 4 field battalions and 1 depot battalion. The field battalions all had 6 companies and the depot 4.

Every company was identical at 140 all ranks. Every regiment was the same at that date. It is equally possible to ascertain establishments for Austrians, with variations for German or Hungarian units, or Russians, with variations for Grenadier or Jäger units.

However, when you look for similar details of British establishments you come up with this:

The problem with Oman’s analysis is that all establishments for Regiments of Foot were by individual battalions and there was no such thing as a Regimental establishment in this period. What Oman has done is to add together every permutation and combination of the 5 main infantry battalion establishments to make the situation seem far more chaotic than it really was.

I therefore carried out a study from the primary source documents, which are all in the National Archives, former Public Records Office, at Kew near London.

The Cavalry, Infantry and various supporting units are in a tight sequential order in the War Office 24 series. WO 379/6 gives monthly locations of all units. This is very useful because apparent anomalies in unit establishments make sense when these are cross-referenced with locations.

Artillery and Engineers were controlled by the Master General of the Ordnance and their establishments are in the WO 55 series, unfortunately not in a tight sequence but spread over several inconsistently titled documents, mostly called Warrants.

I transcribed all the detailed establishments for every unit of the entire British Army in the period 1802-1815 and analysed this data in various ways.

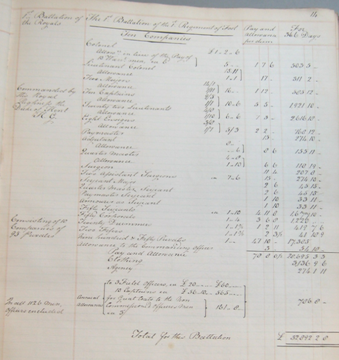

The original data was all held in Ledgers looking like this. They are organised in Financial Years from Christmas Day to Christmas Eve the following year. Most of the Irish establishments are missing, having been lost in a fire in Dublin Castle in the 19th century. However, those for 1813-14 are in the archives and show establishments no different to those in Great Britain. Units moved to and from Ireland fairly frequently so it is possible to see establishments before they went and when they returned. More often than not there was no change whilst they were away, so I was able to reconstruct all the Irish establishments.

The first thing that strikes you is that the ledgers are exactly that, financial ledgers with red ruled bookkeeping columns on the right of each page, and all the establishments are fully costed.

This is the establishment of 1st Battalion, 1st Regiment of Foot (Royal Scots) for the year 25 December 1808 to 24 December 1809. So that it is easier to read, I have transcribed a copy below.

This establishment shows the overall structure of the battalion as 10 companies of 95 privates, the normal way of defining it in the period. It lists every rank, and how many personnel there were in that rank. The first column then gives the pay per day for one man in each rank, the next column the total pay for all men in that rank for one day, and the third column the total cost of everyone in that rank for the complete year. This carries down all the ranks, with various allowances added, until you arrive at the grand total cost for this battalion for the year of 32,642 pounds, 17 shillings and 10 pence.

This is then added into totals for all the infantry, cavalry etc, plus supplementary sheets giving in-year increases or decreases, and finally summed into a total for the entire army for the year. This total was then presented to Parliament for them to authorise that cost for the Army for the year, without which the Army had no legal right to exist. That tight Parliamentary financial control of the Army, to prevent a Monarch using it against the people, dates from the 17th Century English Civil War and the system was only changed late in the 20th Century.

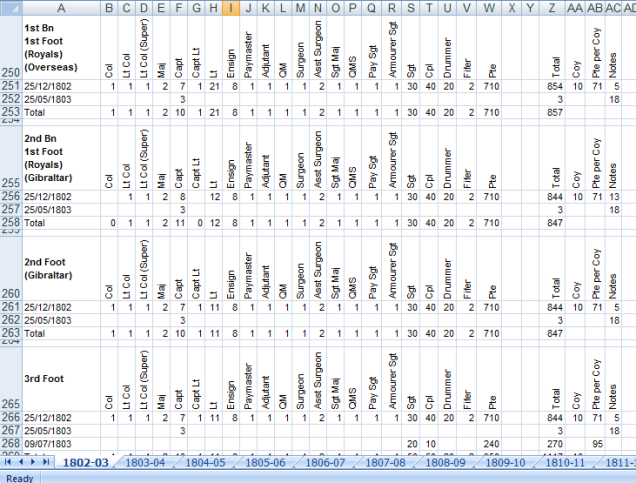

When I started transcribing the establishments, they were all in the format above. It was taking me a day to transcribe each ledger, so to make my task easier, I designed a spreadsheet, with all of the ranks across the top, and all of the units down the left side. I printed off copies of these and could then pencil in how many men of each rank were in each unit (only pencils are allowed in the National Archives Reading Rooms). The one below has the figures typed in from the actual ones which I transcribed in pencil at the National Archives, but the format is the same. I had a different sheet for each year.

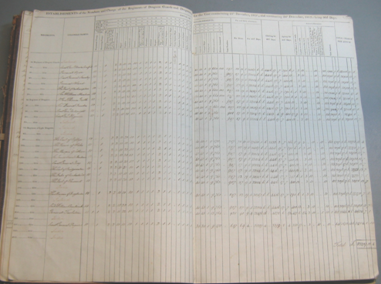

What really astounded me, was when I reached 1811, the format of the ledgers changed, to a version virtually the same as my spreadsheet, with the ranks across the top of a double page and the units down the left side, all preprinted, so the clerks just had to ink in the figures themselves. So a ledger clerk, 200 years ago, had designed the same system which I thought I had just invented. Clearly, great minds think alike!

Infantry Establishments

It is best to start by considering the establishments of the Regiments of Foot, because once you understand their structure it is easier to understand the others.

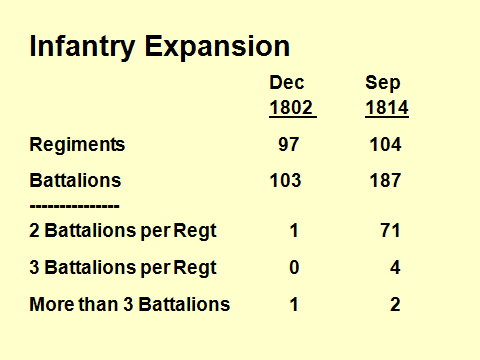

In December 1802 there were 97 Regiments of Foot, all single battalion regiments apart from 1st Foot with 2 battalions and 60th Foot with 6, a total of 103 battalions. At the height of the expansion, in September 1814, there were 104 Regiments, with a total of 187 Battalions. 71 Regiments had two Battalions, 4 had 3, 1st Foot had 4 and 60th Foot had 8.

Most battalions had 10 companies but a few 2nd Battalions had less than this for short periods. In December 1802 most battalions had 750 Rank and File, that is the Corporals and Privates who stand in the ranks (sideways) and the files (front to back) in each battalion. This structure was phased out within 2 years and replaced with a range of 5 different sizes, 400, 600, 800, 1,000 and 1,200.

The new structure was based on modules of 1 corporal and 19 privates. The term module was not in use at the time but it accurately describes the system. Here you can see a module comprising 2 Ranks of 10 Files.

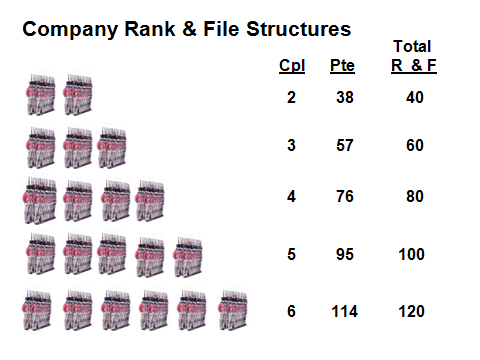

There were 5 possible company rank and file structures, based on a minimum of 2, or maximum of 6, modules.

Almost all battalions consisted of 8 centre companies, 1 grenadier company and 1 light company. The detailed structure of the centre companies is shown here.

The larger companies had 2 lieutenants and the smaller ones only 1. The number of sergeants was the same as that of corporals. There were always 2 drummers per company, regardless of size.

- 1 Drummer per Battalion became Drum Major from Dec 1810.

- 1 Sergeant per Company became Colour Sergeant from Dec 1813.

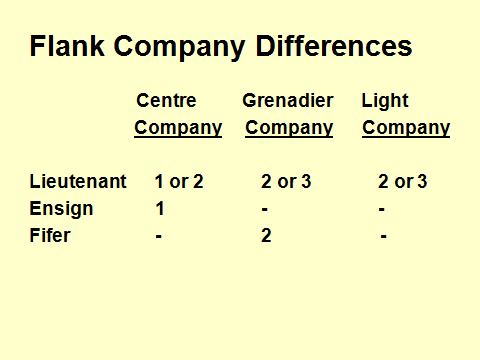

Flank companies, that is grenadier and light, had no ensigns, but an extra lieutenant instead. The number of Lieutenants depended on the size of the battalion, as with the Centre Companies. Grenadier companies had fifers, and were the only companies to do so, so their presence in a battalion establishment is an indication of that battalion having a Grenadier Company, as similarly the number of Lieutenants and Ensigns can make it easy to determine whether they were established for flank companies.

There were a few variations to this standard structure…

- Originally 3 companies per Battalion were commanded by the Colonel, senior Lieutenant Colonel and senior Major, so there were only 7 Captains per Battalion. After May 1803 all companies were commanded by Captains.

- 7th Royal Fusiliers had no Ensigns so had 2 or 3 Lieutenants in all companies. This did not apply to 21st or 23rd Fusiliers.

- Battalions in India and West Indies had 3 subalterns per Company, regardless of strength. Some Battalions in West Indies were reduced to 400 Rank & File from higher establishments, but were then authorised 1 extra Sergeant and 1 extra Corporal per Company.

- Surprisingly, Light Infantry and Rifle Battalions were established for Grenadier & Light Companies, although whether they actually used them in practice is not clear. It may have just been to ensure that they had the additional Lieutenants which flank companies were entitled to. From Dec 1809 Light Infantry and Rifle Battalions all had 3 subalterns, 1 extra Sergeant and 1 extra Corporal per Company.

- From 1809 there was a regular Battalion in Australia and this had an extra Veteran Company, always 100 Rank & File, regardless of structure of remainder of Battalion.

All Battalion headquarters had similar structures, with some minor variations:

- 1st battalions had a Colonel, normally a General, so actual command was with the lieutenant colonel.

- 2nd,3rd and 4th Battalions all had the same headquarters structure as each other.

- Battalions of 600 Rank and File or smaller had only 1 assistant surgeon.

- The new 2nd Battalions had no Paymaster or Pay Sergeant until Dec 1804. Several 2nd Battalions had no Pay Sergeant after that date, although numbers this applied to steadily declined.

- There was a new post of Schoolmaster Sergeant from December 1811.

There were some other variations….

- 60th Foot had Colonel in Chief for the Regiment and Colonel Commandant for every Battalion. 95th Rifles had this same structure from Dec 1809.

- Battalions existing prior to Dec 1802 originally had 2 Lieutenant Colonels. After Dec 1804 only Battalions overseas did so and after Dec 1806 only Battalions in India did so. All new 2nd Battalions had only 1 (unless in India).

There was a considerable expansion of the infantry during the wars.

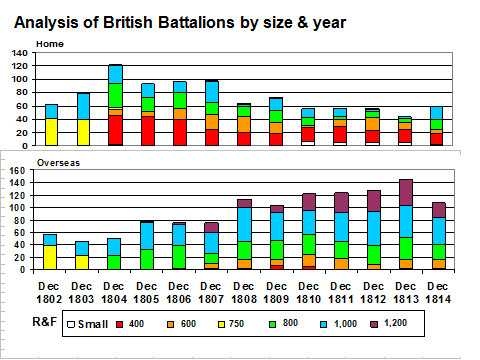

The upper chart shows the number of battalions at home, in Great Britain or Ireland, whilst the lower chart shows those overseas.

The battalions in each stack are colour coded by size, the few small non-standard 2nd battalions are shown as white, the rest in a rainbow of increasing sizes.

Home based battalions were originally all on 750 R & F but in December 1802, some 1st Battalions were increased to 1,000. All the 2nd Battalions formed in the first 2 years were also on 1,000. Overseas the Battalions in India were on 1,000 and those elsewhere on 750.

The 750 structure was then phased out with most becoming 800, and a few 1,000. In Dec 1804, 44 new 2nd Battalions were raised at home, most of 400 R & F, a few of 600. After that most battalions at home were of 400 or 600 R & F with a few on higher establishments as an immediate reserve. Overseas, most battalions in active service areas were of 1,000 R& F with an increasing number on 1,200. Eventually by 1813, 42 Battalions were on the 1,200 structure.

A few overseas Battalions were of 800 R & F, mainly in static garrisons. Some single battalion Regiments serving in the West Indies, were reduced to 600 or even 400 R & F, but after a few years most of these were brought home. These reduced battalions were often allowed to retain their original numbers of sergeants and corporals. Reducing the authorised strength of battalions which were clearly going to be understrength anyway made sense, since that funding could then be used to increase battalions elsewhere, or make an overall saving in the Army budget. In Dec 1814 the army was reduced, mainly by disbanding 22 x 2nd battalions. A number of battalions returned home from overseas, so that the proportion of home battalions on larger 800 or 1,000 establishments was higher than it had been for a few years.

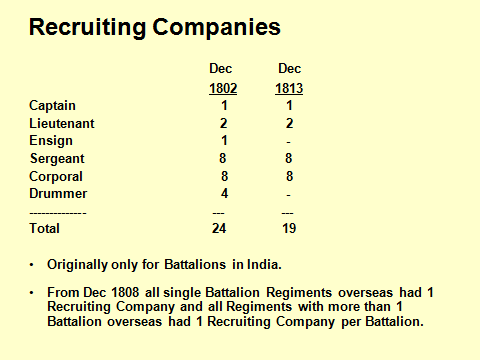

Some Regiments were authorised to have additional Recruiting Companies. Originally this applied only to those in India, but from 1808 all single battalion Regiments serving overseas were authorised to have an additional Recruiting Company, whilst those multi-battalion Regiments with more than one battalion overseas were authorised to have an additional Recruiting Company for every battalion.

There were a number of Regiments of Colonial infantry. The term “colonial” was not in use at that time but it reasonably describes units raised for service in West Indies, Canada, and Africa.

When the New South Wales Regiment became the 102nd Foot in 1808, and the New Brunswick Regiment became the 104th Foot in 1810, they adopted standard British establishments.

There was also a separate list of Foreign Regiments.

By Dec 1805 the 10 Battalions of King’s German Legion all had 8 companies of 100 R&F, with no flank companies. Some increased to 8 x 120 in Dec 1807. They provided their skirmishers by the Hanoverian system of detaching a few files of designated rifle armed sharpshooters from each of their companies.

All increased to 10 companies of 100 in Dec 1811, but still had no official authority for flank companies. In practice however flank companies were formed, as recorded by Johann Maempel, who served in 7th KGL and stated that whilst they were in Sicily in July 1812, an order arrived from England to form Grenadier and Light companies. In consequence the Sharpshooters were all concentrated into the new Light Company, which therefore became rifle armed. Edmund Wheatly, a British officer serving with 5th KGL confirms this structure by stating that he was in the Grenadier company.

Most of the KGL battalions, having discharged their non-Hanoverian personnel at the end of the Peninsular War, were reduced to 10 companies of 60 in Dec 1814 (actually at Waterloo they operated as 6 companies of 100 with the surplus 91 officers and 104 sergeants detached to the Hanoverian Landwehr).

I have left the Foot Guards to the end of the Infantry, because they had a different structure to all other British infantry, which will come as no surprise to anyone who has served in the British Army, since the Foot Guards still do have unique features.

They were the only infantry to have Regimental establishments, rather than Battalion ones. Their authorised establishment showed a Headquarters, combining the staff of all battalions, and the total number of companies of each type in the entire Regiment.

Their Centre company structure was as follows:

The Foot Guards had a normal structure for flank companies with additional Lieutenants, but no ensigns, in Grenadier or Light Companies and they had Fifers in Grenadier Companies.

- 1st Foot Guards had one extra Grenadier and one extra Light Company.

- From Dec 1813 to Sep 1814, 1st Foot Guards had 3 extra companies whilst Coldstream and 3rd Foot Guards had 2 extra each, probably all used as Light Companies.

- Foot Guards Centre Company structures were similar to other infantry, but were very large. From December 1809 – Sep 1814 they had more Sergeants and Corporals per company than was normal and in December 1814 they reversed the usual proportion of Lieutenants to Ensigns.

The Foot Guards Regimental Headquarters structure contained enough staff for 3 Battalions of 1st Foot Guards and 2 battalions each for the Coldstream and 3rd Foot Guards.

It is possible that companies were not permanently assigned to particular battalions, but were treated as a pool from which to draw the requisite number of companies to make up battalions as required. Sometimes detachments of a number of companies plus an ad-hoc headquarters were used, as at Cadiz in 1809-10.

- The Foot Guards had only 1 Lieutenant Colonel per Regiment, not 1 per Battalion, and only 1 Major per Battalion.

- Foot Guards Regiments had no Paymasters or Pay Sergeants.

- From Dec 1814, 1st Foot Guards increased to 3 Battalion Surgeons, whilst Coldstream and 3rd Foot Guards increased to 2 each.

- Originally 1 Drum Major per Regiment, increased to 3 for 1st Foot Guards, and 2 each for Coldstream and 3rd Foot Guards, with compensating reductions in Drummers, from Dec 1810.

- 1 Schoolmaster Sergeant per Battalion from Dec 1811.

- 1 Sergeant per Company became Colour Sergeant from Dec 1813.

- All three Regiments had a Solicitor and a Deputy Marshal.

- 1st Foot Guards had 3 Hautbois, or Oboe players.

- 1 Provost Marshal was shared by all 3 Regiments of Foot Guards.

Cavalry Establishments

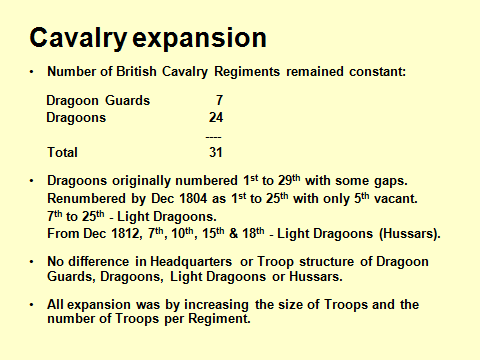

The number of British Cavalry Regiments remained constant throughout the period.

Regiments had a number of Troops, organised as 2 per Squadron, although the term Squadron does not appear in establishments

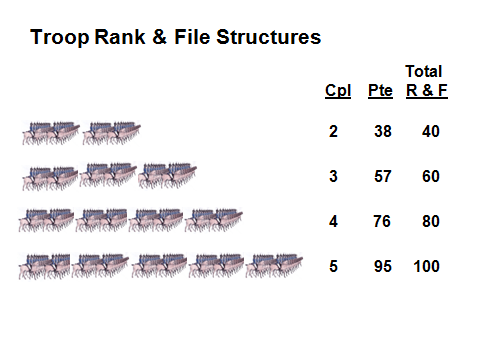

Cavalry used the same modular system as infantry, with 1 Corporal to 19 Privates.

Troop Rank and File structures were the same as Infantry companies but there was no 120 Troop structure.

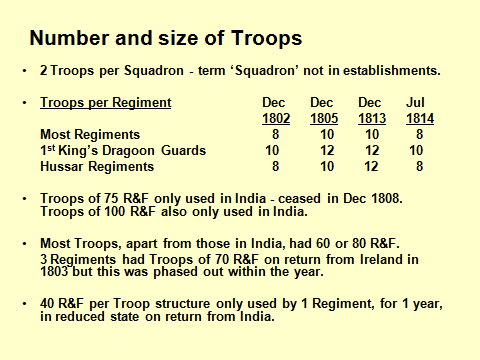

The number of Troops per Regiment varied:

The number of Troops per Regiment varied:

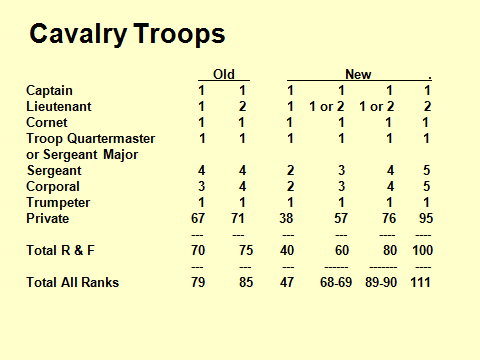

.The detailed Troop structure was:

- The largest Troops, 100 Rank and File, had 2 Lieutenants as did most of those smaller ones when deployed overseas.

- Just 1 Trumpeter per Troop, unlike the Infantry who had 2 Drummers per company.

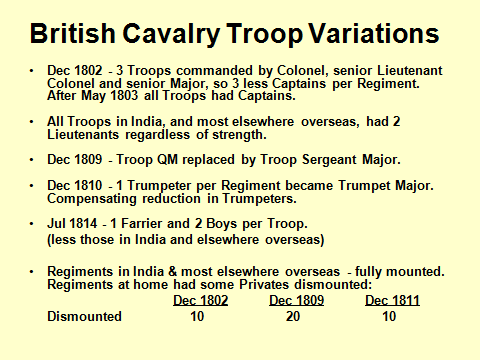

Variations to the standard Troop structure were:

Cavalry Regimental Headquarters were similar to Infantry Battalion Headquarters.

- Regiments in Great Britain had only 1 Lieutenant Colonel from Jul 1814.

- They always had 2 Assistant Surgeons, regardless of size.

- Regimental Quartermasters were authorised from December 1809, the same date as Troop Sergeant Majors replaced Troop Quartermasters.

- All Regiments had a Schoolmaster Sergeant from Dec 1811.

- 3rd Dragoons had extra post of Kettle Drummer, granted by King George III in 1778 in recognition of their capturing two silver kettle drums at the Battle of Dettingen in 1743.

Just like the Infantry there was an expansion of the Cavalry during the wars, however this was achieved by increasing the number of Troops, and the size of those Troops, as opposed to raising any new Regiments.

Those Cavalry Regiments serving in India were authorised to form additional Recruiting Troops, although the normal system was for Regiments going overseas to leave two Troops (one Squadron) behind as a Depot.

There were a number of Regiments of Foreign Cavalry. There was no Colonial Cavalry.

- From Dec 1811, the KGL Heavy Dragoons re-titled as Dragoons and KGL Light Dragoons as Hussars. In Dec 1813, Dragoons re-titled as Light Dragoons but establishment unchanged.

- Originally all KGL Cavalry had same establishment of 8 Troops of 76 R & F. All, apart from 3rd Hussars, adopted a standard British 10 x 80 structure in Dec 1811, and 3rd Hussars did so the following year. In December 1812 3rd Hussars increased to 12 Troops of 80. In Dec 1814 most all Regiments, apart from 1st and 3rd Hussars reduced to 10 x 60.

- Brunswick Hussars always had 6 Troops of 100 R & F. This Regiment was still in British Service in Mediterranean in 1815, whilst a new Regiment, in Brunswick service, was at Waterloo.

I have left the Household Cavalry to end of the Cavalry section, because they used different structures to other Cavalry Regiments. The Royal Horse Guards (Blues) were not formally given Household Cavalry status until 1820, but this is not apparent from their establishment, which had many features in common with the 1st and 2nd Life Guards and were unique to those three regiments, so I have included them within the general designation of Household Cavalry.

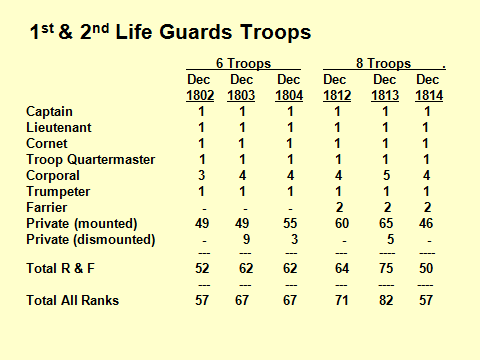

The 1st and 2nd Life Guards Troop structure was:

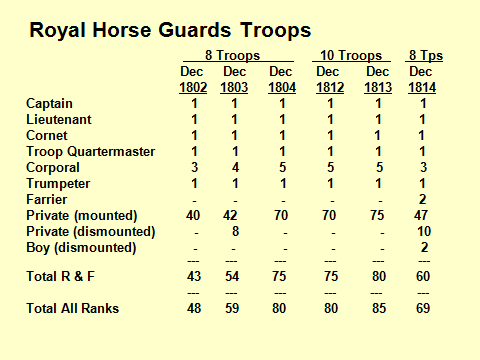

The Royal Horse Guards Troop structure was:

- Whereas Foot Guards companies were of the largest size used by Infantry, Household Cavalry had smaller Troops and less Troops per Regiment than other Cavalry.

- Only 1 Lieutenant per Troop, even when overseas.

- They had no rank of Sergeant but did not have twice as many Corporals.

- They retained Troop Quartermasters and did not have Troop Corporal Majors.

- At times some Privates were dismounted.

Household Cavalry Regimental Headquarters structure was:

- Royal Horse Guards had only 1 Lieutenant Colonel from Jul 1814.

- No Regimental Quartermasters.

- No Paymasters or Pay Corporals.

- The Royal Horse Guards had a Trumpet Major. 1st & 2nd Life Guards did not have this post.

- All three Regiments had a Kettle Drummer.

- 1st and 2nd Life Guards shared a Marshal. 1st Life Guards had a supernumerary Chaplain until December 1805.

- All Regiments had a Schoolmaster Corporal from Dec 1811.

- Only 1 Assistant Surgeon until December 1812.

- 1st & 2nd Life Guards had 2 Veterinary Surgeons each from Dec 1813.

Artillery Establishments

The Artillery came under the Board of Ordnance and, unlike Infantry and Cavalry, establishments were not issued every year. An establishment would be issued and then, from time to time, amendments would be made, so it is necessary to trace the last complete establishment and add all the cumulative amendments to this. Sometimes, after a number of amendments, a complete new establishment would be authorised. In some cases it was necessary to go back to 1783 in order to understand the later structure.

The Royal Artillery was commanded by the Master General of Ordnance, who was a senior General, holding a post in the Government Cabinet. His staff comprised:

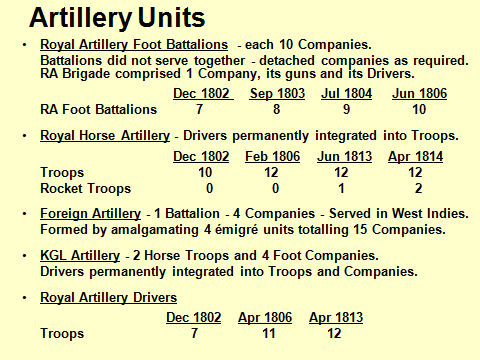

The Royal Artillery had Battalions, each of 10 Companies. Battalions did not serve together but detached companies to tasks as required. Royal Artillery Battalion Headquarters therefore had no operational role but nevertheless had a similar structure to Infantry Battalion Headquarters. The term “brigade” was used to describe a Company, its guns (from a Park) and, if mobile, a detachment of Drivers.

- RHA was like one additional battalion. Unlike Foot Companies, drivers were permanently integrated into Troops.

- Foreign Artillery consisted of 1 small Battalion of 4 Companies, formed by amalgamating 4 émigré units totalling 15 Companies. It served in West Indies. Companies had same structure as British Foot Companies.

- KGL Artillery had a Headquarters similar to a Royal Artillery battalion with 2 Horse Troops and 4 Foot Companies. Structure was similar to British RHA and Foot Companies except that drivers were permanently integrated into both Troops and Companies.

Royal Artillery Battalion Headquarters had a similar structure to Infantry Battalion Headquarters, but did not serve in the field as formed Headquarters. Their personnel were used to provide artillery staff for headquarters and garrisons.

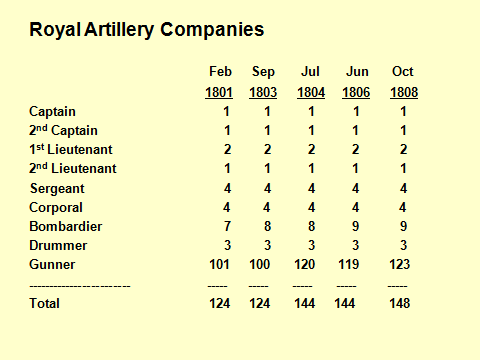

Royal Artillery Company structures remained reasonably constant, although there was some growth.

One extra Bombardier was authorised in September 1803, with a compensating reduction of 1 Gunner. It should be noted that Bombardiers were junior to Corporals, equivalent of modern Lance-Bombardiers. In July 1804, 20 Gunners were added. In June 1806, Bombardiers were further increased by 1, again with a compensating reduction of 1 Gunner. In October 1808, 4 more Gunners were added.

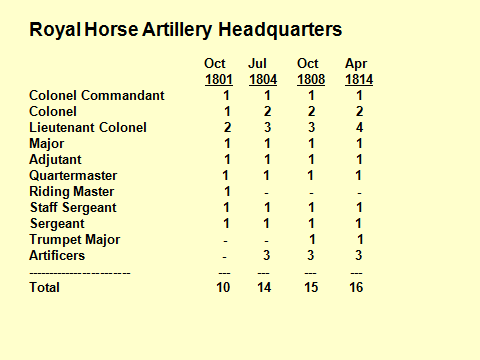

The RHA had a similar Headquarters to Royal Artillery Battalions.

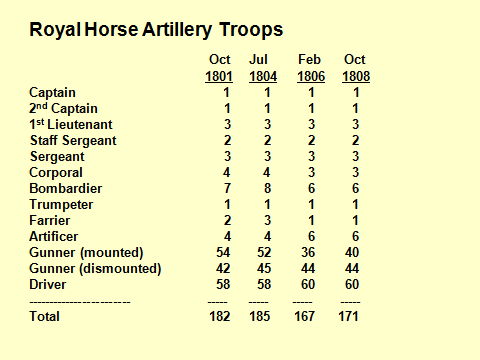

RHA Troop structures were:

RHA Troops had no 2nd Lieutenants so their officers were more experienced than those of RA Companies (just like in infantry grenadier companies). Their structures remained reasonably constant, although there was a reduction in the number of Corporals, Bombardiers and Gunners at the same time as the number of troops was increased from 10 to 12 in February 1806. Artificers comprised Smiths, Collar Makers and Wheelwrights. Unlike RA Companies, RHA Troops had permanently assigned Drivers, and these were additional to the separate establishment of Royal Artillery Drivers.

The dismounted gunners rode on the limbers and ammunition wagons of their troop. Each RHA Troop was issued with Desaguliers limbers to pull their five guns (the one howitzer being pulled by an older style “A” frame limber) and these Desaguliers limbers had seats for two gunners. In addition to this, each of the six artillery pieces in the troop had an accompanying ammunition wagon, which for the RHA was an articulated limber wagon comprising a standard Desaguliers limber pulling a second Desaguliers limber modified to carry four ammunition boxes. These ammunition limber wagons could carry a total of six dismounted gunners, two on the leading limber and four more on the rear one. Each RHA troop therefore had limber seats for up to 46 dismounted gunners. In addition to this there were three further Desaguliers limber wagons in each troop, on a scale of one per two-gun section, but because they were held in reserve they did not normally carry gun crews.

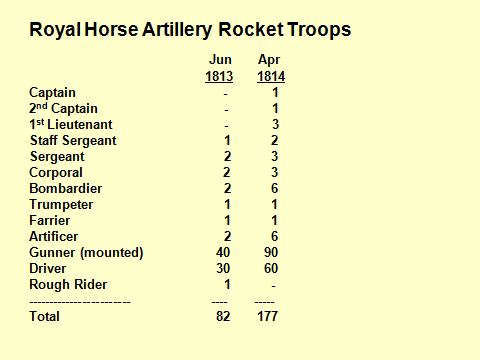

An RHA Rocket Troop was originally authorised in June 1813 as a detachment to be added to a normal RHA Troop. In April 1814 this structure was replaced by two full Rocket Troops.

Unlike normal RHA Troops, all of the gunners in the RHA Rocket Troops were mounted. Each Troop had six Rocket Cars, which were converted Desaguliers limbers, with a pair of ammunition boxes behind each other in the centre, and long boxes containing rocket sticks down each side. Rocket launcher troughs were carried on each of the long side boxes, and the heavier rockets could be fired from these whilst still attached to the Rocket Car, or separate, as required. The Rocket Cars were towed by standard Desaguliers limbers.

Each gunner in the Rocket Troop also had four light rocket heads, carried in a pair of saddlebags. They also each carried a bundle of four rocket sticks, which made them look like lancers from a distance. Indeed one Rocket Troop commander went so far as to issue his men with lance pennons, although these were entirely unofficial. These gunners could be deployed in three man sections, one of the three having a light rocket trough behind his saddle. Two men could dismount and fire up to 12 light rockets between them, a very cost effective way of producing artillery firepower, although the accuracy of the rockets left something to be desired.

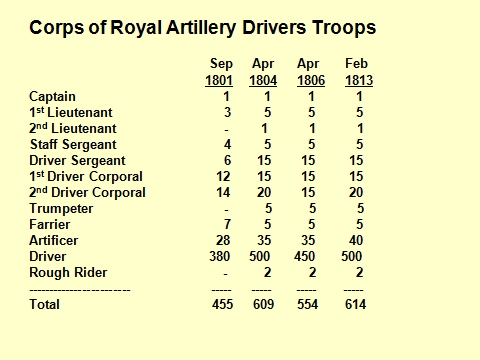

The Corps of RA Drivers had a small Headquarters commanded by Royal Artillery Officers.

It had very large Troops by normal standards and they were clearly designed to operate as 5 semi-autonomous sections, which could then be attached to Foot Companies. The Troop size increased in April 1804, reduced slightly in April 1806, on expansion from 7 to 11 Troops and was finally expanded to its largest size in February 1813.

Included in the artillery structure were four French émigré units serving in the West Indies. On paper they comprised 15 companies totalling 1,821 all ranks. In practice a return given in response to a Parliamentary question gave their actual strength in November 1800 as 846 all ranks.

On 11 April 1806 a new establishment was issued for the Corps of Foreign Artillery, which was an amalgamation of all the former émigré units. It had a small battalion headquarters staff of one major, one sergeant-major and one quartermaster sergeant.

The Foreign Artillery comprised four companies which were identical to those of the Royal Artillery of 19 June 1806, apart from the fact that rather than 119 gunners, they had only 116 plus three non-effectives. There is no record of subsequent changes to this establishment. The unit served in the West Indies throughout the Napoleonic wars.

On 1 August 1806 the King’s German Legion artillery was placed under the direction of the Master General of the Ordnance and on the same footing as the Royal Artillery. The KGL headquarters staff was similar to a RA battalion headquarters.

The KGL Artillery structure was as follows:

KGL Artillery had two Horse Troops, three Light Foot Brigades and one Heavy Foot Brigade. One major difference compared to British Artillery was that the foot units were called Brigades, not Companies, because they had their own Drivers and their own guns. This structure remained unchanged for the remainder of the war, apart from the formation of a Depot Company and Garrison Company in 1813.

Engineers Establishments

The 2 engineer corps, the Royal Engineers and the Royal Military Artificers also came under the Master General of Ordnance.

The Royal Engineers was an all officer Corps which expanded from 113 officers to 262 during the Napoleonic Wars.

- They had no permanent sub-unit structure but were used as a pool from which to detach teams of officers to tasks as required.

- The post of Chief Engineer had been discontinued in May 1802 but the Master General of Ordnance appointed the senior Royal Engineer officer as Director of Fortifications and Works.

The Royal Military Artificers had a small Headquarters commanded by Royal Engineer officers.

Its Companies were mainly artisan tradesmen, capable of carrying out a wide range of construction tasks.

- In Dec 1802 they comprised 10 Companies, Sep 1806 – 12 Companies, May 1811 – 32 Companies.

- Originally had labourers but in Sep 1806 all Privates became skilled tradesman. In May 1811 proportion of Miners significantly increased undoubtedly in response to the needs of siege warfare in the Peninsula

- They never had more than 1 Sergeant Major and/or 1 junior officer per company, the rest being provided from the Royal Engineers, although no set scale was given, as this depended on the task in hand.

- In Apr 1812 they were re-titled as Royal Sappers and Miners but this made no change to their establishment.

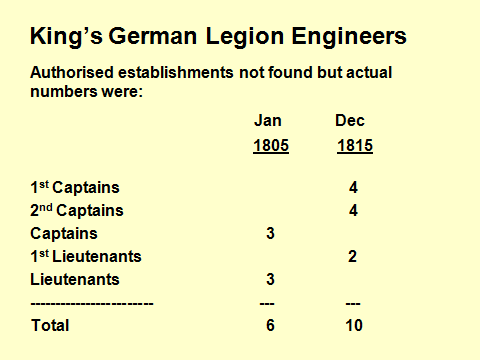

There were also a small number of King’s German Legion Engineers, who were attached to the Royal Engineers and carried out exactly the same duties.

Supporting Troops Establishments

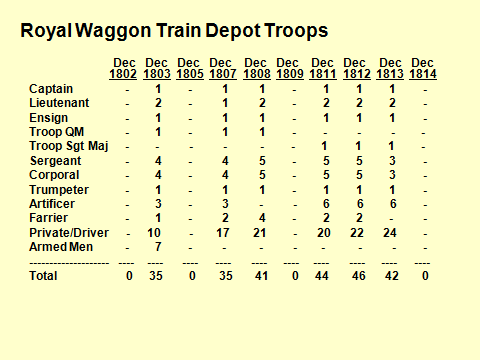

The term “support” was not in vogue during the Napoleonic wars, but I have used it to categorise the Royal Waggon Train, Royal Staff Corps and Staff Corps of Cavalry, all of whose establishments are included in the main WO 24 ledgers along with the Cavalry and Infantry.

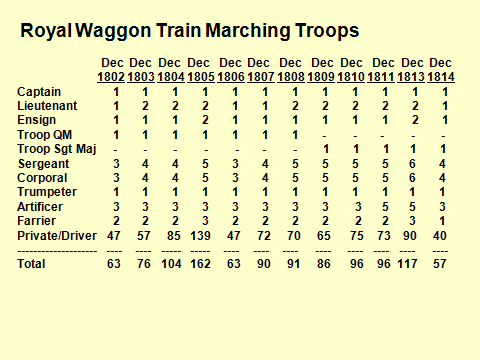

The Royal Waggon Train was mainly used to provide an ambulance service and transport some small arms ammunition. The Headquarters, of a similar structure to a Cavalry Regiment, was increased or decreased almost every year.

The Royal Waggon Train had Marching Troops for field service. The number of troops was changed almost every year, constantly increasing and decreasing. Not only did the number of Royal Waggon Train Troops change every year, but so did the establishment of those troops.

It also had Depot Troops for home service, whose establishment was also constantly changing.

The Royal Waggon Train had a poor reputation, with one officer describing it as “Fat Colonel Hamilton and his useless Waggon Train”, but constantly changing an organisation’s structure is a recipe for creating demoralisation and inefficiency.

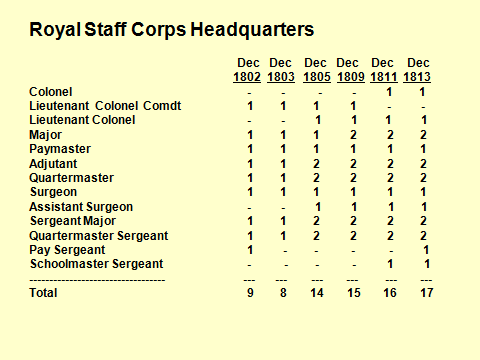

The Royal Staff Corps a Headquarters similar to an Infantry Battalion.

It had 4 companies in Dec 1802, 7 in Dec 1803 and 10 in Dec 1809.

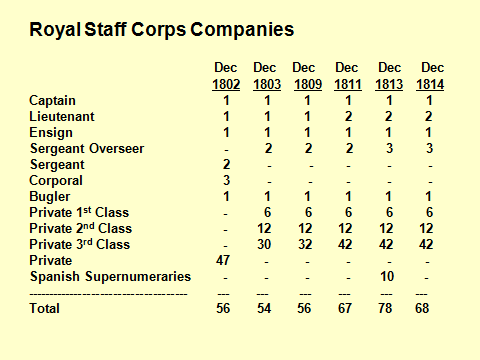

Royal Staff Corps companies were gradually expanded in size during the Napoleonic Wars. Various studies have suggested that they were effectively combat engineers, but unlike the Royal Military Artificers they had no skilled artisan tradesmen. They had an unusual structure of Privates 1st Class, 2nd Class and 3rd Class, and these titles do not reflect their real status.

Sergeant Overseers were paid the same as Infantry Sergeant Majors, Privates 1st Class more than Infantry Sergeants, Privates 2nd Class more than Infantry Corporals and Privates 3rd Class more than Infantry Privates. They were clearly designed to supervise large working parties of unskilled labour, whether infantry or civilians and in some ways they can be seen as the forerunners of the Royal Pioneer Corps.

Sergeant Overseers were paid the same as Infantry Sergeant Majors, Privates 1st Class more than Infantry Sergeants, Privates 2nd Class more than Infantry Corporals and Privates 3rd Class more than Infantry Privates. They were clearly designed to supervise large working parties of unskilled labour, whether infantry or civilians and in some ways they can be seen as the forerunners of the Royal Pioneer Corps.

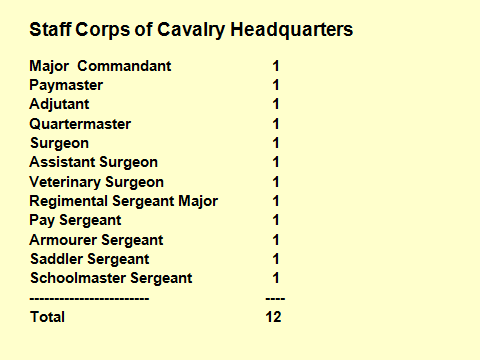

The Staff Corps of Cavalry was formed in Dec 1813 with HQ and 4 Troops to act as couriers and military police. Disbanded in Oct 1814, re-formed by Dec 1815, but not clear if this was in time for Waterloo.

It had a Headquarters structure similar to a Cavalry Regiment, although with no Colonel or Lieutenant Colonels and only one Major.

The 4 Troops of the Staff Corps of Cavalry had a small, non-standard, Cavalry Troop structure.

To sum up:

- British establishments were fully costed and were clearly the result of compromises between the Army and the Treasury.

- If Unit strength fell significantly below establishment then establishment was reduced and budgetary savings were used to fund increases elsewhere. Good old Treasury principle of use it or lose it, still in force until recently.

- Location was clearly a major factor in deciding Battalion size. Establishments balanced troops to tasks as required, so that units in active service theatres were authorised to have high strengths, some at home at high strengths were in immediate reserve, whilst those with a home service role were at lesser strengths.

- The modular structure allowed for easy expansion or reduction as required.

- It is noteworthy that the drafters of these establishments showed considerable preparedness to make amendments if circumstances required it.

The Duke of Wellington made a quote about his planning process, as follows:

British establishments were constructed in a similar way to Wellington’s tactical plans, not rigid, but pragmatic and flexible, so they could easily be adapted to changed circumstances.